The world knows Norman Rockwell as the quintessential painter of American life—a master of nostalgia who captured baseball games, holiday dinners, and the heartwarming innocence of small-town existence. His iconic covers for the Saturday Evening Post, totaling 321 over 47 years, became cultural shorthand for the nation’s idyllic best. Yet, the story behind the canvas is a profound study in contradiction: a man who dedicated his life to painting joy, warmth, and family unity while secretly battling crippling anxiety, intense depression, and devastating personal loss. The reality of Norman Rockwell’s life was far darker than his sun-drenched canvases suggested, culminating in a dramatic late-career shift that risked everything he had built to finally paint the unvarnished truth.

The Outsider Who Painted Belonging

Born in Harlem, New York City, on February 3, 1894, Rockwell’s early life was marked by a deep sense of being an outsider. He was skinny, clumsy, and felt perpetually disconnected from his peers and even his own parents. Drawing became his refuge, a world he could control and an emotional escape. By listening to his father read Charles Dickens, he learned how to paint people with words, a skill he would later translate into images, using humor and exaggerated features to cope with his profound feelings of awkwardness.

This early sense of isolation propelled him into a relentless pursuit of belonging, which he channeled directly into his art. By the time he was 14 in 1908, he left high school to enroll in the Chase School of Fine and Applied Art, taking daily train commutes and studying everything from life drawing to human anatomy under masters like George Bridgeman. He quickly realized his genius lay not in fine art, but in illustration—the art of telling stories people could feel.

His meteoric rise was unprecedented. At just 18, he landed his first major commission. By 1913, at the age of 19, he became the full-time art editor of Boy’s Life magazine, a position unheard of for someone so young. This intense, early success became his first cross to bear. By 1916, his first cover graced the Saturday Evening Post, marking him as a national star before he was even 25. He was painting the American Dream, but the speed of success was overwhelming, and behind the scenes, he was starting to fall apart.

The Hidden Price of Perfection

Despite the external glory, Rockwell was plagued by doubt and a feeling of being a fraud. He once admitted that he felt his “ability to draw… didn’t count for much.” Around 1911, he started feeling deeply insecure about every aspect of his life, a chronic anxiety that intensified with fame. By 1920, the pressure of deadlines and the impossible expectations of being the nation’s illustrator led to what was quietly called a nervous breakdown. He had to step away entirely to recover. This cycle of intense work followed by emotional collapse would define his life.

His personal life offered little solace. His first marriage to Irene O’Coner in 1916 was troubled from the start. He was obsessed with his work, neglecting everything else, and later heartbreakingly confessed that she “didn’t love” him. The marriage limped along for nearly 14 years before ending in divorce in 1930. Just months later, he remarried Mary Barstow, a math teacher 14 years his junior, and they quickly had three sons: Jarvis, Thomas, and Peter.

Yet, happiness remained elusive. By 1933, the nervous exhaustion returned, forcing him back into hospitalization. That same year, a trip to Europe, meant to reignite his passion by studying Rembrandt and the Old Masters, only deepened his despair. He spiraled into depression, calling himself a fraud whose Post covers were meaningless compared to the true greats. The darkness was so profound that he contemplated ending his life.

The family moved to Arlington, Vermont, seeking peace on a 60-acre farmhouse, but their home became a quiet battleground. Mary struggled severely with alcoholism and depression, a situation Rockwell chronicled in his journals, noting her distance and anger when drinking. In 1939, seeking clarity, he began therapy with famed psychoanalyst Eric Ericson, a relationship that provided a crucial breakthrough. Ericson helped Rockwell see that his paintings of happy, warm families were not just art—they were an attempt to heal his own lonely childhood and fulfill the emotional warmth his cold and distant mother had never provided.

The Flames and the Fury of Change

The 1940s were defined by further stress and the emergence of a new, politically engaged Rockwell. In 1943, his entire studio in Vermont tragically burned down, a blaze that consumed hundreds of paintings, props, costumes, and personal items, a loss valued at over $1.5 million in today’s money. While officially an accident, the incident included rumors of arson following a dispute with a neighbor, leaving the painter devastated by the total destruction of his physical history.

Paradoxically, the same year, he created two of his most lasting works. He finished the Four Freedoms paintings, based on President Roosevelt’s speech, which were initially rejected by the Post. Rockwell believed in them so much he paid for the project himself. The subsequent tour raised $132 million for war bonds (over $2 billion today). Simultaneously, he painted Rosie the Riveter, an image of female strength that infuriated many male readers who canceled subscriptions, demonstrating the hidden politics always bubbling beneath his art.

The personal pain continued to escalate. Mary’s mental health deteriorated further during the 1940s and 1950s, necessitating psychiatric care at the Austin Riggs Center. In 1953, the family moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, specifically so Mary could be closer to the treatment center, where she received electroshock therapy. While his public art showed the perfect small town, his reality was one of endless medical bills, isolation, and fear. His own doctor, Eric Ericson, once delivered a devastating assessment: “You paint your happiness but you don’t live it.”

The Painting That Shattered the Myth

The breaking point arrived in 1963. After 47 years and 321 covers, Norman Rockwell made the monumental decision to leave the Saturday Evening Post. He was 69, tired, and felt the world had moved on from his style of sanitized nostalgia. He was particularly frustrated with the magazine’s strict editorial limits, which prevented him from showing black Americans in anything but background or servant roles. “I portrayed the best of all possible worlds,” he admitted, “That kind of stuff is dead now.”

He joined Look magazine in 1964, a move that gave him the complete freedom he craved to tackle current affairs, civil rights, and social injustice. This was his great, risky final act, and the blowback was immediate and severe. He received streams of hate mail, accusing him of being a “race traitor” and threatening his life for daring to paint black children or depict racism.

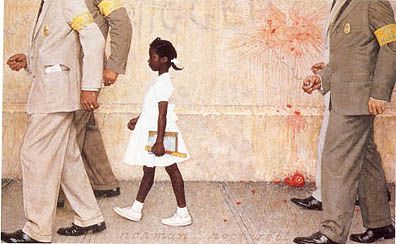

That same year, he produced his most explosive and important work: The Problem We All Live With. It depicted Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old black girl, walking to her desegregated New Orleans school, escorted by U.S. Marshals. Behind her, the wall was defiled with racial slurs and the smear of a splattered tomato. It was a raw, shocking image of American truth that instantly tore the veil of pleasant illusion.

Readers were furious. Thousands canceled their subscriptions to Look. But Rockwell, finally painting what he truly felt, did not stop. Later in 1964, he poured five weeks of sleepless, tormented effort into Murder in Mississippi, a painting reflecting the horrific murder of civil rights workers James Cheney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. The painting was raw, lit by the ominous glow of killers’ torches, and deeply painful—a necessary act of witnessing and moral outrage.

The Final Confession

In his final decades, Rockwell continued to use his paintbrush to atone for the racial stereotypes he had sometimes used earlier in his career (such as in his illustrations for Mark Twain). He sought out civil rights groups and activists, determined to show black people not as victims, but as heroes of their own stories. He changed, he listened, and he fought until the end.

His third marriage in 1961 to Molly Punderson, a retired teacher, finally brought a measure of stable domestic order to his chaotic life. He was 67, and in his own pragmatic words, he married her because she was organized and he desperately needed help managing his business affairs and his life.

Rockwell received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977, the highest civilian award, though he was too sick to attend the ceremony. He died on November 8, 1978, at the age of 84. The true, agonizing depth of his lifelong struggle with mental health was revealed only after his death, when it was discovered he had nearly $200,000 in unpaid therapy bills. The bills—a quiet, ledgered confession—told the story his painted world never could.

Norman Rockwell’s legacy endures not because he simply painted happiness, but because he spent a lifetime battling for it, both on the canvas and in his soul. He gave us the illusion of a perfect America, then, with courage and pain, he showed us the truth of the one we actually lived in. His final, groundbreaking work proved that even the painter of the ideal could ultimately find his most powerful voice in facing the harsh realities of the real world.

News

⚡ The Wrench of Destiny: How a Single Dad Mechanic Saved a Billionaire’s Empire—and Her Heart

Part I: The Grounded Queen and the Man Who Listens The rain was not a gentle shower; it was a…

😱 Janitor vs. CEO: He Stood Up When 200 People Sat Down. What He Pulled From His Pocket Changed EVERYTHING!

Stand up when you talk to me. The words cut through the ballroom like a blade. Clara Lane sat frozen…

FIRED! The Billionaire CEO Terminated Her Janitor Hero—Until Her Daughter Whispered The Impossible Truth! 😱💔

The marble lobby of HailTech gleamed under cold fluorescent lights. Victoria Hail stood behind her executive desk, her manicured hand…

The $500 Million War: How Chris Brown’s Eternal Rage and Secret Scars Defined a Billion-Dollar R&B Empire

The name Chris Brown doesn’t just evoke R&B dominance; it conjures a storm. It is a name synonymous with talent…

Integrity Crisis: Mortgage Fraud Indictment Explodes as AG Letitia James’s Grandniece is Charged for Allegedly Threatening Elementary School Official

The very foundation of accountability, the bedrock principle championed by New York Attorney General Letitia James throughout her career, appears…

The Chronological Crime Scene: Explosive New Evidence Suggests Meghan Markle’s Age Rewrites Her Entire Royal Timeline

The Chronological Crime Scene: Explosive New Evidence Suggests Meghan Markle’s Age Rewrites Her Entire Royal Timeline In the highly…

End of content

No more pages to load