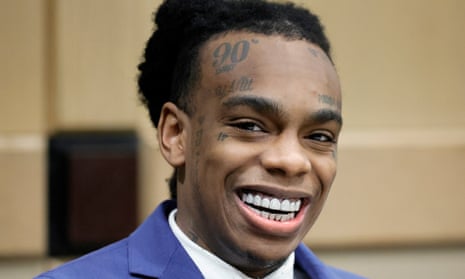

In a dramatic and often contentious appeal hearing for rapper YNW Melly, born Jamell Demons, the state’s prosecution faced an unprecedented grilling from appellate judges. At the core of the judicial scrutiny were concerns over the alarming breadth of search warrants, the questionable handling of digital evidence—particularly cell phone records and social media accounts—and the controversial application of legal doctrines like “independent source” and “inevitable discovery.” The implications of this hearing could significantly weaken the state’s murder case against Melly, potentially leading to further delays or even a dismissal of crucial evidence.

The hearing commenced with a sharp rebuke from Judge Gross regarding the initial search warrants issued in the case. “The problem that I’m having with these warrants is that they’re initially they were so broad,” Judge Gross stated, expressing surprise that trial judges ever signed off on them. He emphasized that law enforcement has a responsibility to “take the bull by the horns initially and narrow the search,” a fundamental principle of search and seizure laws. This sentiment resonated deeply, suggesting a systemic issue with how digital data was initially requested and obtained by investigators.

One of the central points of contention was the expansive scope of warrants that sought “the entirety of these social media accounts” to merely identify the owner. The judges questioned the necessity of such sweeping access when the objective was ostensibly much narrower. Prosecutors initially acknowledged the broadness of their requests, even mentioning the intention to use a “taint team”—a group meant to sift through evidence to ensure only relevant information is used and illegally obtained data is excluded. Yet, as Melly’s defense attorney highlighted, this crucial safeguard “never happened.” Instead, law enforcement allegedly gained unfettered access to all data, deciding unilaterally what was relevant and what wasn’t.

The hearing revisited Judge John Murphy’s prior ruling, which suppressed key pieces of evidence, including cell phone records and related forensic data. Judge Murphy had concluded that law enforcement’s methods violated Melly’s constitutional rights, a decision that, if upheld, would severely undermine the state’s ability to link Melly to the crime. The defense’s argument centered on the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, asserting that the state’s warrants lacked the necessary particularity and probable cause.

A significant portion of the debate revolved around the state’s reliance on the “independent source” and “inevitable discovery” doctrines. These legal principles allow for the admission of evidence that was initially obtained illegally if it can be proven that the evidence would have been discovered through lawful means, independently of the misconduct. The prosecution leaned heavily on the testimony of Detective Polo, who joined the case years after the initial incidents. Detective Polo claimed that even with a narrower scope, he “would have found” the same incriminating information through his later investigation into gang activity and witness tampering.

However, this argument faced fierce skepticism from the appellate judges. Judge Gross directly challenged the inherent hindsight bias in Polo’s testimony: “Isn’t that easy to say in hindsight? And how do you distinguish between every case in which sure, in hindsight, vision is 20/20?” The defense further exposed the speculative nature of Polo’s claims, noting that his investigation was initiated four years after the shootings, not concurrently with the initial warrants. Critically, Detective Polo had already reviewed all the data obtained under the original, broad warrants before making his retrospective assessments, raising concerns that he couldn’t genuinely separate illegally obtained information from what he would have discovered. The defense lawyer powerfully argued that such a retrospective analysis, heavily reliant on “speculation” and “hindsight,” undermines the very purpose of Fourth Amendment protections.

Moreover, the defense pointed out that the state had previously withdrawn its argument regarding Melly’s “standing”—his legal right to challenge the search—during the initial trial court proceedings. This withdrawal, according to the defense, meant the state could not reintroduce the argument at the appellate level, further eroding their position. The affidavits supporting the warrants themselves, according to the defense, implicitly established Melly’s ownership of the phones, contradicting the state’s later attempts to question his standing.

The trial court’s attempt to “save the state’s bacon” by imposing temporal limitations on the warrants was also scrutinized. While the trial judge narrowed some warrants to a few weeks or months, the defense argued that this “temporal severability” was a novel and potentially dangerous approach in Florida law. Such a practice, they contended, could incentivize law enforcement to seek overly broad warrants with the expectation that courts would later narrow them, effectively bypassing constitutional safeguards.

Another critical exchange focused on the practical limitations of data retrieval from technology companies. Prosecutors argued that companies like Apple lacked the capacity to sort data with narrow parameters, forcing law enforcement to request vast quantities of information. However, the judges questioned why law enforcement wouldn’t be required to attempt more precise search terms or temporal limits, pushing the burden back onto investigators to adapt to modern digital realities rather than casting overly wide nets.

The overarching sentiment from the appellate bench was clear: law enforcement must exercise greater precision and adhere strictly to Fourth Amendment principles when dealing with digital evidence. The days of obtaining “the entirety of somebody’s social media account for something as narrow as identity” appear to be numbered, especially without a clear, demonstrable need. The lack of a “taint team” and the reliance on speculative hindsight testimony were significant blows to the prosecution’s appellate arguments.

The video concludes with the observation that the state’s appeal was a deliberate tactic to delay the trial, giving them more time to prepare. This claim, if true, paints a concerning picture of the strategic use of legal processes to compensate for investigative shortcomings. The appellate judges have taken the arguments under advisement, leaving the future of YNW Melly’s high-profile murder trial hanging in the balance. The outcome of this appeal will not only shape the fate of a celebrity but could also establish critical precedents for how digital privacy and evidence are handled in criminal cases across Florida.

News

⚡ The Wrench of Destiny: How a Single Dad Mechanic Saved a Billionaire’s Empire—and Her Heart

Part I: The Grounded Queen and the Man Who Listens The rain was not a gentle shower; it was a…

😱 Janitor vs. CEO: He Stood Up When 200 People Sat Down. What He Pulled From His Pocket Changed EVERYTHING!

Stand up when you talk to me. The words cut through the ballroom like a blade. Clara Lane sat frozen…

FIRED! The Billionaire CEO Terminated Her Janitor Hero—Until Her Daughter Whispered The Impossible Truth! 😱💔

The marble lobby of HailTech gleamed under cold fluorescent lights. Victoria Hail stood behind her executive desk, her manicured hand…

The $500 Million War: How Chris Brown’s Eternal Rage and Secret Scars Defined a Billion-Dollar R&B Empire

The name Chris Brown doesn’t just evoke R&B dominance; it conjures a storm. It is a name synonymous with talent…

Integrity Crisis: Mortgage Fraud Indictment Explodes as AG Letitia James’s Grandniece is Charged for Allegedly Threatening Elementary School Official

The very foundation of accountability, the bedrock principle championed by New York Attorney General Letitia James throughout her career, appears…

The Chronological Crime Scene: Explosive New Evidence Suggests Meghan Markle’s Age Rewrites Her Entire Royal Timeline

The Chronological Crime Scene: Explosive New Evidence Suggests Meghan Markle’s Age Rewrites Her Entire Royal Timeline In the highly…

End of content

No more pages to load