Sam Cooke’s Fury: The Seven Artists He Quietly Branded as “Sellouts”

In the history of American music, Sam Cooke stands as both a saint and a skeptic. The silky tenor who gave the world “A Change Is Gonna Come” and “You Send Me” was not only a voice of hope but also a witness to betrayal. For Cooke, music was never just a career—it was the marrow of his soul, a language forged in poverty, prayer, and pain. But behind the charm and composure, Sam Cooke harbored unspoken wounds. He believed that some of the very artists the world adored had betrayed the roots of the music they claimed to sing.

He never shouted it in interviews, never launched public crusades. But in quiet hotel rooms, late-night recording sessions, and half-empty whiskey glasses, Sam spoke. He named names. And to him, they weren’t icons, but sellouts.

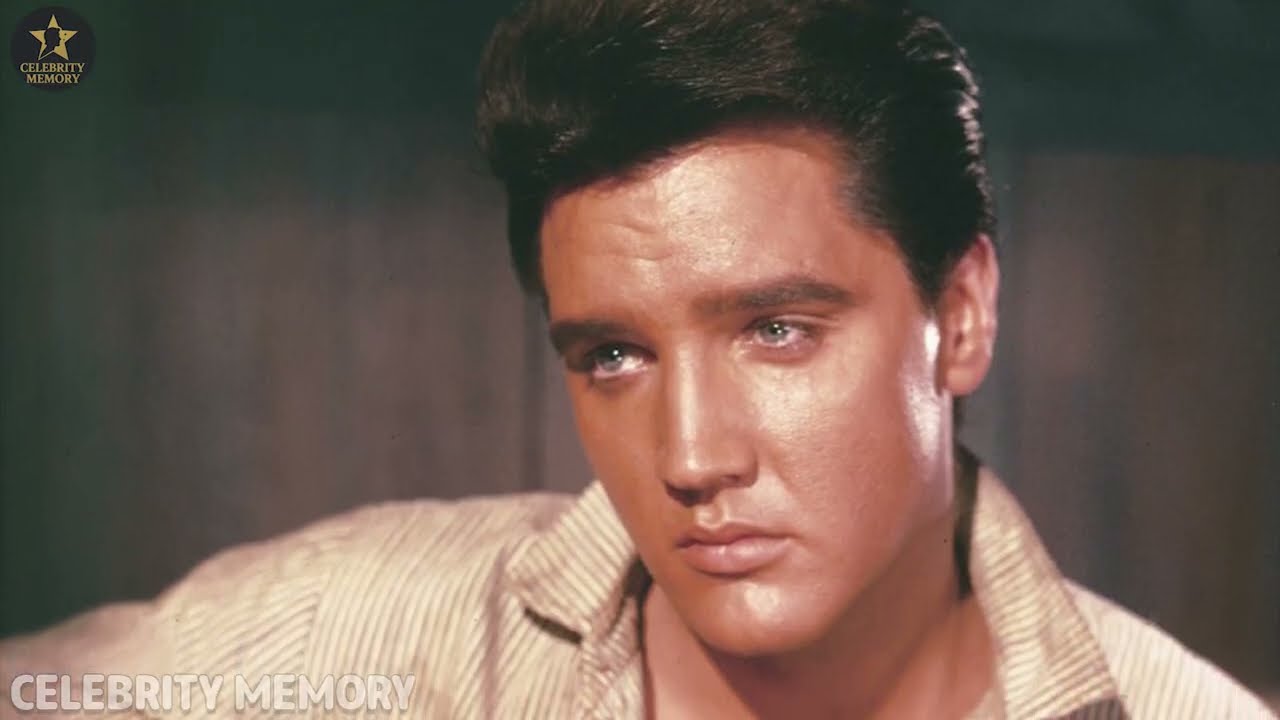

Elvis Presley: The Polished Puppet

Sam Cooke never despised Elvis Presley. In fact, in the beginning, he respected him. Elvis had talent, charisma, and a voice that made crowds swoon. But for Sam, respect slowly turned into disillusionment.

Cooke grew up in the church—his father a preacher, his earliest stages dusty wooden pulpits in Chicago. Gospel wasn’t performance. It was survival, a cry from the depths of Black life in America. Rock and roll, born from gospel, blues, and the sweat of Black labor, carried that same essence of pain and resistance.

Then came Elvis, smiling in his white suit, hips shaking, singing the same rhythms—but stripped of their roots. “They love the sound, but not the struggle,” Sam once sighed, pointing at a television where Presley was performing.

The betrayal ran deeper than performance. Presley’s breakout hit, “That’s All Right,” was borrowed from Arthur Crudup, a Black man who lived in poverty and died nearly penniless. Elvis earned millions. Crudup got crumbs. Cooke knew this wasn’t merely music—it was erasure, a rewriting of cultural history where the source was ignored.

Even worse was Presley’s silence. When Nina Simone, James Brown, Marvin Gaye, and Cooke himself risked careers by standing with the Civil Rights movement, Presley stood aside. Sam called him a “polished puppet”—an entertainer who performed as though the world were fine while fire hoses and police dogs tore through the South.

Sam once declined a joint performance with Elvis. Not out of spite, but because he refused to play the role of “token Black singer” placed onstage to prove harmony. For him, Presley wasn’t evil. He was simply the product of a system that crowned a King while burying its creators.

Mick Jagger: The Blues in Costume

Few things pained Sam more than hearing Mick Jagger sing the blues. Jagger, to the world, was wild, electric, magnetic. But to Cooke, it was theater.

“He sings like he’s wearing a costume,” Sam told an RCA engineer after hearing “Come On” by the Rolling Stones. The issue wasn’t talent—Sam knew Jagger had it. The issue was authenticity. Mick Jagger, a middle-class Englishman, rasped out blues notes with a growl he had never lived. He imitated the pain of Howlin’ Wolf and Otis Redding without ever knowing the sting of racial humiliation or the ache of working-class struggle.

Sam once peeked into a Stones party in 1964, then turned and walked away. “Children playing with pain,” he muttered. To him, it was worse than mimicry. It was usurpation. Black artists like Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley remained sidelined, while British imitators reigned on American charts.

Sam summed it up in one line that cut like a knife: “That boy wants the blues, but the blues don’t want him.”

Aretha Franklin: The Sister Who Sold Prayer

Perhaps the deepest disappointment for Sam wasn’t a white artist at all, but someone from his own world—Aretha Franklin.

They had known each other since their gospel days. Aretha’s father, Reverend C.L. Franklin, often invited Sam to sing at church services. To Sam, Aretha’s voice was “a voice that touched God.” But when she signed with Atlantic Records and was crowned “The Queen of Soul,” Sam grew uneasy.

Her voice, once raw and sacred, now seemed polished for mass consumption. Songs like “Respect” soared to the top of the charts, but Sam grimaced—not because they were bad, but because they were crafted for marketability. “She had a voice that touched God,” he once said, “but God was no longer the audience.”

Sam never hated Aretha. He felt sadness, as if watching a younger sister stray from the church into a world of glitter and contracts. Where he founded his own label, SAR Records, to preserve artistic freedom, she accepted the industry’s embrace. To him, it was the “easy path”—crowded, lucrative, but soulless.

Ray Charles: The Vegas Betrayal

Ray Charles was a genius. No one denied it—not even Sam. But to Cooke, Charles represented a different kind of sellout: the quiet betrayal of choosing luxury over responsibility.

Ray once poured gospel fire into his music. But as the 1960s wore on, Sam saw him slipping into Vegas lounges, dressed in white suits, crooning to white audiences. “Ray sold soul for show business,” Sam remarked backstage after a show.

For Sam, it wasn’t about jealousy. It was about responsibility. He believed soul music was meant to remind people of their pain, to keep the memory of suffering alive. Ray, in his eyes, traded that role for applause in casinos while civil rights marches filled the streets.

The Others: Voices That Disappeared

Elvis, Jagger, Aretha, and Ray were the most glaring names. But Sam named others too—singers and performers who, to the public, were heroes, but to him had abandoned authenticity. Some were peers who let their gospel roots fade into polished pop. Others were idols who allowed contracts and radio play to water down their voices.

“They don’t sing anymore,” Sam once told a friend. “They perform.”

The Price of Integrity

Sam Cooke’s life ended violently in 1964, long before he could fully articulate these grievances to the world. But in the recordings he left behind—especially the haunting “A Change Is Gonna Come”—his philosophy shines through.

To Sam, music was prayer. It was cracked, imperfect, trembling with authenticity. He founded his own label, refused lucrative contracts, and declined to stand on stages that asked him to play the role of token. He demanded authenticity not just from himself, but from everyone who called themselves soul singers.

That demand made him enemies. It also made him timeless.

Why Sam’s Criticism Still Matters

The debate Sam Cooke raised hasn’t vanished. Today, discussions of cultural appropriation, authenticity, and responsibility echo the same questions he asked in smoky rooms sixty years ago. Who gets to profit from music born of suffering? Who preserves the struggle within the sound, and who polishes it for easy consumption?

Sam’s words about Elvis and Jagger may sound harsh. His disappointment in Aretha may seem unfair. His critique of Ray Charles may feel judgmental. But in the end, Sam wasn’t attacking individuals as much as he was pointing to a system—a machine that rewards those who play along and erases those who resist.

Sam Cooke never hated these artists. He simply mourned what they had lost.

And so, while the world remembers him for his honeyed voice, his quiet fury deserves to be remembered too. Because Sam Cooke’s real message wasn’t just that “a change is gonna come.” It was that change requires honesty. It requires artists to sing not for applause, not for contracts, but for truth.

Full video:

News

“NFL STAR Travis Hunter STUNS Fans, QUITS Football FOREVER After SHOCKING BETRAYAL — Teammate SECRETLY Slept With His Wife and the SCANDAL That No One Saw Coming Has ROCKED the Entire League!”

Travis Hunter’s Shocking Exit: The Jaguars Star, His Wife Lyanna, and the Scandal That Could Shatter a Locker Room When…

“Rapper T.I. BREAKS HIS SILENCE With SHOCKING CONFESSION After His Son King Harris Gets SLAPPED With 5 YEARS Behind Bars — What He Reveals About The Arrest, The TRUTH Behind The Charges, And The DARK FAMILY SECRETS That NO ONE Saw Coming Will Leave You Absolutely Speechless!”

TI’s Worst Nightmare: King Harris Arrested, Facing 5 Years in Prison For years, T.I. warned the world that his son…

At 48, Jaleel White FINALLY Reveals the CHILLING Final Words Malcolm Jamal Warner Whispered to Him Before His Mysterious Death — A Secret He’s Kept Silent For Decades That Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About Their Friendship, Hollywood’s Dark Side, and What Really Happened in Those Final Moments (NEVER Told Until NOW!)

Jaleel White Breaks His Silence: The Untold Story of His Final Goodbye to Malcolm-Jamal Warner The news of Malcolm-Jamal Warner’s…

Christina Ricci Just SHOCKED Hollywood By EXPOSING The DARK Truth About Ashton Kutcher – What She Revealed Has Fans DEMANDING He ROT In Jail… The Secrets, The Lies, And The Scandal That Could Finally END His Career Forever!

Christina Ricci’s Warning and the Dark Shadow Over Ashton Kutcher For years, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis were seen as…

“Ozzy Osbourne’s FINAL Words Before His Death Leave Fans STUNNED – What He Revealed in That Heartbreaking Last Message Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About the Prince of Darkness Forever, and the Truth Behind His Shocking Goodbye Is Sending Shockwaves Across the Music World Right Now!”

Ozzy Osbourne’s Final Act: How the Prince of Darkness Orchestrated His Own Farewell When fans first heard Ozzy Osbourne mutter…

“Kelly Rowland BREAKS Her Silence at 44 – The Stunning CONFIRMATION Fans Have Waited Decades to Hear Is Finally Out, and It’s So Explosive It Could Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé, and the Secret Truth She’s Been Hiding All Along… Until NOW!”

Kelly Rowland’s “Dirty Laundry” of Fame: Secrets, Rumors, and the Shadows of Destiny’s Child For decades, Kelly Rowland has been…

End of content

No more pages to load