The Show That Terrified Network Television: The Rise and Destruction of Roc

In the early 1990s, American television was flooded with sitcoms that kept things light, digestible, and advertiser-friendly. Families laughed along to Married with Children, Melrose Place, and even The Cosby Show. But for a brief window between 1991 and 1994, one series slipped through the cracks of corporate control and dared to tell the truth. That show was Roc—a working-class sitcom starring Charles S. Dutton that began as harmless comedy and quickly became the most politically dangerous program on network television.

Its destruction wasn’t accidental. It was systematic, deliberate, and revealing of how corporate media handles Black voices that refuse to conform. To understand how Roc became both groundbreaking and threatening, we first have to understand the extraordinary man who brought it to life.

From Prison to the Stage: Charles S. Dutton’s Transformation

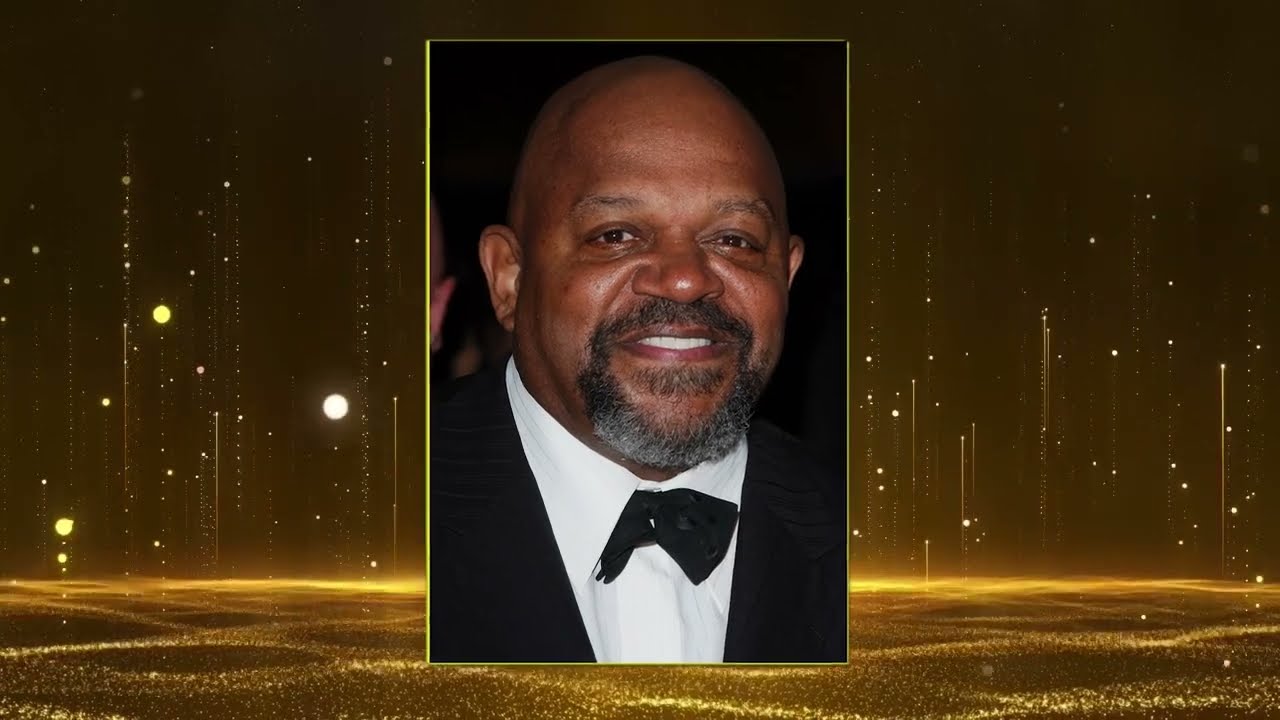

Charles Stanley Dutton was not supposed to succeed. Born in Baltimore in 1951, his youth followed a tragically predictable path—poverty, violence, and incarceration. At 17, he was convicted of manslaughter after a fight turned fatal. He spent much of the 1970s in prison, where the system was evolving into the mass-incarceration machine we know today. But unlike most inmates, Dutton found salvation in an unlikely place—literature.

Three days in solitary confinement changed his life. In his cell, he discovered an anthology of Black playwrights. Upon release from isolation, he gathered 101 fellow prisoners and directed a play called The Day of Absence. He knew nothing about directing, but he had found his calling. Prison officials allowed him to continue—on the condition that he earn his GED and pursue college courses. By the time he walked free in 1976, he had an education, a passion for theater, and a vision for something bigger.

Dutton enrolled at Towson State University, then Yale School of Drama, where he met playwright August Wilson. Wilson recognized his raw authenticity and cast him in productions that captured the realities of Black life without caricature. Dutton’s Broadway debut in 1984’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom earned him a Tony nomination, followed by another in 1990 for The Piano Lesson. He was no longer a prisoner or a statistic—he was one of the country’s most respected stage actors.

How Roc Was Born

By the early 1990s, television executives began circling. They wanted Dutton for his charisma and credibility, but they wanted him on their terms. When HBO Independent Productions approached him with the idea of a Black version of The Honeymooners, Dutton agreed—but only with conditions. He demanded control over casting, bringing in stage collaborators Carl Gordon and Rocky Carroll. He refused to include children, famously telling the Baltimore Sun: “Cosby had 55,000 of them, and I didn’t want ankle-biters running around.”

Most importantly, he wanted authenticity. He and co-creator Stan Daniels went to Baltimore to study real sanitation workers. They met John Wood, a city garbageman whose quiet dignity inspired the character of Roc Emerson. This insistence on grounding the show in reality would become both its greatest strength—and its death sentence.

The Experiment That Shook Fox

Roc premiered on August 25, 1991, in Fox’s Sunday primetime slot. On paper, it looked like another sitcom. Roc Emerson was a garbage collector, his wife Eleanor a nurse, his father a retired old-timer, and his brother a charming freeloader. The formula seemed safe.

But within weeks, it was clear this wasn’t another Cosby Show. Unlike sanitized middle-class Black sitcoms, Roc dealt directly with drug addiction, unemployment, gang violence, and systemic racism. Roc didn’t just crack jokes; he analyzed, challenged, and refused to serve as comic relief for white audiences.

Then came Season 2. In an unprecedented move, the cast performed the entire season live. That meant no editing, no second takes, and—crucially—no way for Fox to censor politically uncomfortable content. Dutton and his cast brought their stage training to television, and what emerged wasn’t just comedy. It was social commentary in real time.

In one unforgettable episode, Roc lamented: “There are more homeless people on the streets and there are times I’m afraid to let my wife walk out the front door.” This wasn’t prime-time escapism. It was a mirror held up to America.

Politics in Prime Time

The show’s boldest move came during the 1992 presidential election. Roc struggled to choose between candidates he believed were hostile to Black interests. The storyline mirrored the real disillusionment many African-Americans felt during that election cycle. For advertisers, this was dangerous territory.

Network executives wanted lighter comedy. But Dutton wasn’t interested in jokes that distracted from reality. He began clashing with the mostly white writing staff, rewriting scripts he felt misrepresented Black experiences. Writers called him “difficult,” a label often slapped on Black performers who demanded control over their own narratives.

Meanwhile, Fox launched Martin—Martin Lawrence’s wildly popular sitcom. Unlike Roc, Martin was loud, exaggerated, and politically safe. It delivered laughs without challenging viewers, and executives wanted Roc to follow suit. Dutton refused.

The Breaking Point

By Season 3, Roc had transformed from sitcom to televised consciousness-raising. Dutton became executive producer, gaining more power but also more responsibility. Fox moved the show from Sundays to Tuesdays—a quiet signal that the network wanted it gone.

The breaking point came with the Season 3 finale, Terrence Got His Gun. Addressing gun violence in Black communities, the episode ended with Dutton breaking the fourth wall. Looking into the camera, he declared:

“Our own kids are doing what 300 years of slavery couldn’t do, what the Ku Klux Klan couldn’t do. They’re threatening our spirit, breaking our hearts, and destroying us from within.”

For Fox, this was unforgivable. Dutton had turned their platform into a pulpit, and advertisers wanted nothing to do with it. By May 1994, Roc was canceled.

The Systematic Destruction

Fox claimed low ratings killed the show. In truth, Roc maintained strong numbers among Black viewers and earned Emmy nominations and NAACP Image Awards. What really doomed it was advertiser discomfort and executive fear of authentic Black political voices.

Fox didn’t just cancel the show—they buried it. Unlike other sitcoms that lived on in syndication, Roc was rarely re-aired, ensuring its cultural impact would be erased. The message to future Black creators was clear: step outside the lines, and you’ll be erased too.

Five months later, BET aired a never-before-seen episode where Dutton delivered a six-minute monologue in near-darkness. Fox had refused to air it, calling it “too downbeat.” In truth, it was too real.

The Legacy of Silence

The destruction of Roc wasn’t an isolated case. That same year, Fox also canceled South Central, In Living Color, and The Sinbad Show, gutting its slate of authentic Black programming. What survived were shows that fit white executives’ comfort zones.

The impact on Dutton was personal. Around the same time, his marriage to actress Debbie Morgan collapsed. He admitted to feeling worthless despite his artistic success. Still, he refused to regret his decisions. “In 73 or 74 episodes of Roc, I don’t think there was a moment of buffoonery,” he later said. “I look at the reruns now on BET, and I’m still pretty proud.”

Dutton eventually found redemption on HBO, directing The Corner in 2000, which won an Emmy and inspired The Wire. The same stories Fox suppressed were hailed as “prestige television” once removed from advertiser-driven network TV. The hypocrisy was obvious.

What Was Lost

The erasure of Roc carried human costs. Carl Gordon (Roc’s father) died in 2010. Heavy D (who played Calvin) in 2011. Rosalind Cash in 1995. Even John Wood, the real sanitation worker who inspired Roc Emerson, died tragically in 2013 after a street altercation. Their deaths weren’t just personal losses—they symbolized the silencing of an entire generation of authentic Black representation.

For 72 episodes, Roc Emerson was a fully realized working-class Black intellectual, a man of dignity and frustration, who dissected America with honesty. That character was something network television had never allowed before—and hasn’t allowed since.

Conclusion: The Price of Truth

The cancellation of Roc wasn’t about ratings. It was about control. It was about drawing boundaries around what Black creators could say and how Black life could be portrayed. In destroying Roc, Fox protected advertisers, preserved stereotypes, and set a precedent that still lingers today.

Charles S. Dutton’s journey—from prison to Broadway to prime time—proved that truth could slip into America’s living rooms, even if only briefly. Roc was erased, but its spirit lives on as a reminder of what’s possible when authenticity refuses to bow to comfort.

The tragedy isn’t just that Roc was canceled. It’s that its destruction succeeded in convincing audiences for decades that such a show could never exist. But for a brief, shining moment, it did. And that alone terrified television’s power brokers more than anything else.

Full video:

News

“NFL STAR Travis Hunter STUNS Fans, QUITS Football FOREVER After SHOCKING BETRAYAL — Teammate SECRETLY Slept With His Wife and the SCANDAL That No One Saw Coming Has ROCKED the Entire League!”

Travis Hunter’s Shocking Exit: The Jaguars Star, His Wife Lyanna, and the Scandal That Could Shatter a Locker Room When…

“Rapper T.I. BREAKS HIS SILENCE With SHOCKING CONFESSION After His Son King Harris Gets SLAPPED With 5 YEARS Behind Bars — What He Reveals About The Arrest, The TRUTH Behind The Charges, And The DARK FAMILY SECRETS That NO ONE Saw Coming Will Leave You Absolutely Speechless!”

TI’s Worst Nightmare: King Harris Arrested, Facing 5 Years in Prison For years, T.I. warned the world that his son…

At 48, Jaleel White FINALLY Reveals the CHILLING Final Words Malcolm Jamal Warner Whispered to Him Before His Mysterious Death — A Secret He’s Kept Silent For Decades That Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About Their Friendship, Hollywood’s Dark Side, and What Really Happened in Those Final Moments (NEVER Told Until NOW!)

Jaleel White Breaks His Silence: The Untold Story of His Final Goodbye to Malcolm-Jamal Warner The news of Malcolm-Jamal Warner’s…

Christina Ricci Just SHOCKED Hollywood By EXPOSING The DARK Truth About Ashton Kutcher – What She Revealed Has Fans DEMANDING He ROT In Jail… The Secrets, The Lies, And The Scandal That Could Finally END His Career Forever!

Christina Ricci’s Warning and the Dark Shadow Over Ashton Kutcher For years, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis were seen as…

“Ozzy Osbourne’s FINAL Words Before His Death Leave Fans STUNNED – What He Revealed in That Heartbreaking Last Message Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About the Prince of Darkness Forever, and the Truth Behind His Shocking Goodbye Is Sending Shockwaves Across the Music World Right Now!”

Ozzy Osbourne’s Final Act: How the Prince of Darkness Orchestrated His Own Farewell When fans first heard Ozzy Osbourne mutter…

“Kelly Rowland BREAKS Her Silence at 44 – The Stunning CONFIRMATION Fans Have Waited Decades to Hear Is Finally Out, and It’s So Explosive It Could Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé, and the Secret Truth She’s Been Hiding All Along… Until NOW!”

Kelly Rowland’s “Dirty Laundry” of Fame: Secrets, Rumors, and the Shadows of Destiny’s Child For decades, Kelly Rowland has been…

End of content

No more pages to load