Ray Charles’ Final Roar: The 10 Artists He Could Never Forgive

When Ray Charles closed his eyes for the last time in 2004, the world mourned a genius. A man who had taken gospel, R&B, jazz, and country and fused them into something indestructible—soul music. But what Ray left behind wasn’t just records, concerts, and an everlasting legacy. He also left behind bitterness, a quiet but unmistakable fury toward those he believed diluted, hijacked, or disrespected the very essence of music.

In a world quick to call Elvis Presley “The King,” Ray saw a very different story. He carried scars from segregation, rejection, and erasure. And before his death, he named names—artists he could never reconcile with. Not necessarily out of personal hatred, but because they represented a system he considered dishonest, exploitative, and soulless.

This is Ray Charles’ unofficial blacklist—the voices, faces, and figures who symbolized everything he refused to bow to.

Elvis Presley: The Spotlight Thief

On a quiet afternoon in Los Angeles, 2002, Ray was asked the question one last time: What do you think of Elvis Presley? His reply was short, sharp, and final:

“Don’t ask me no more questions about Elvis. All he did was take our music and make money from it.”

For Ray, Elvis was not a villain but a symbol. He didn’t accuse him of stealing directly—but of being lifted by an industry that happily ignored black pioneers until a white face could carry their sound into America’s living rooms. Elvis danced the same dances, sang the same gospel-infused shouts, but he was crowned a revolutionary while men like Ray fought for radio airplay.

Ray never forgave the system that made Elvis a king while the architects of the sound remained unnamed.

Pat Boone: The Whitewash

Ray didn’t even say his name. He just called him “that white boy singing it back.” Boone’s clean-cut renditions of Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” or Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” made him a household idol. Meanwhile, the originators were excluded from the same stage lights.

Ray turned the radio off whenever Boone’s voice came on. Not because Boone was bad—he sang smoothly enough—but because he was empty. To Ray, Boone’s polished voice was a fraud: a cover-up that replaced lived pain with commercial safety.

“He sings like he’s reading someone else’s speech,” Ray muttered once.

It wasn’t Boone the man he despised, but the machine that celebrated his palatable imitation while ignoring the raw soul from which the music was born.

Michael Bolton: Wearing Another Man’s Skin

By the early 1990s, Michael Bolton was hailed as the new “soulful” voice of America. His soaring ballads filled stadiums, his duets with Pavarotti earned him international respect, and his rendition of “Georgia on My Mind” drew standing ovations.

But when asked about Bolton, Ray whispered: “That boy sings like he’s wearing my skin.”

It wasn’t personal hatred. Bolton had talent, discipline, and power. But to Ray, his success was another cruel joke—everything Ray had once been criticized for, Bolton was celebrated for. When Ray sang with raw emotion, he was “too black.” When Bolton sang the same way, he was “groundbreaking.”

Ray summed it up: “I’m not mad he took my voice. I’m mad they gave it a new name.”

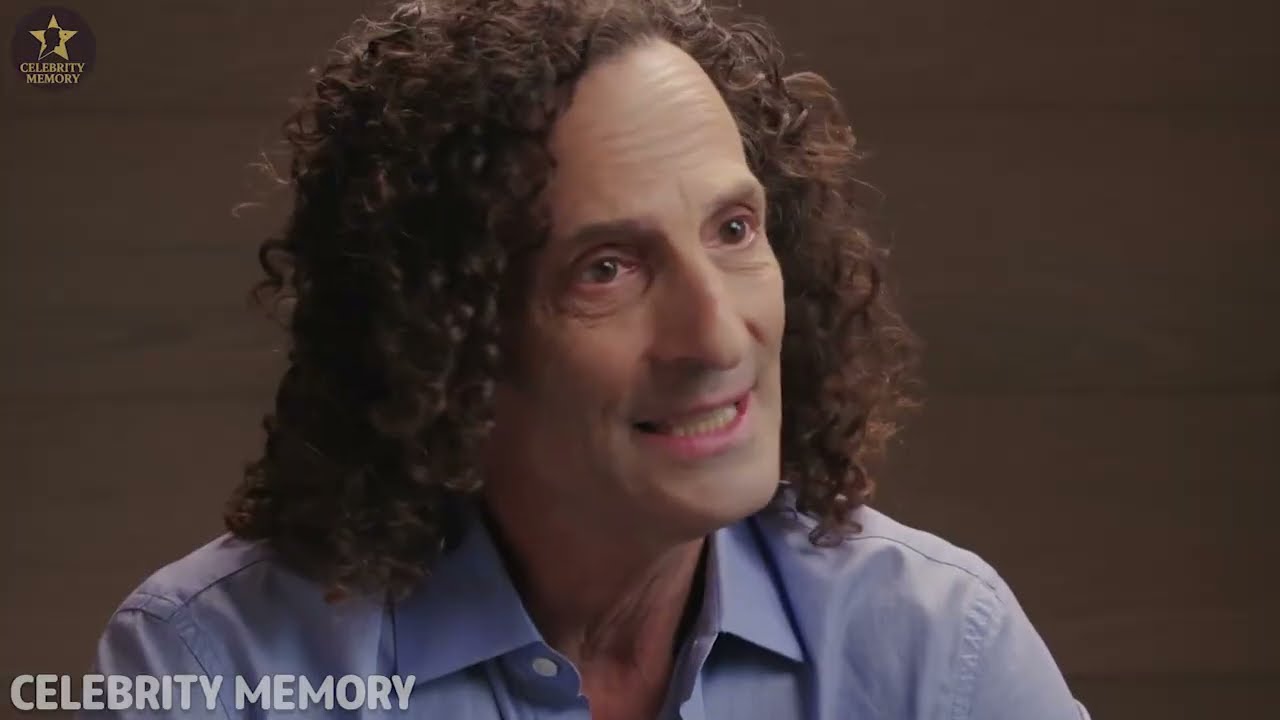

Kenny G: The Death of Jazz

Ray once said, “If Charlie Parker came back to life and listened to the radio today, he’d throw his horn in the river.”

Everyone knew he was talking about Kenny G.

To Ray, Kenny G was not offensive, just too safe—jazz stripped of its grit, chaos, and truth. Smooth saxophones playing in hotel lobbies didn’t sound like rebellion; they sounded like surrender.

“Jazz isn’t something to be background music for hotel dinners,” Ray insisted. “Jazz is something that makes people get up from their seats and live.”

To Ray, Kenny G represented a new danger—not outright theft, but the slow sedation of a genre that had once screamed with fire.

Teena Marie: The Mirror Without Scars

Teena Marie was beloved by the black community and even championed by Rick James and Motown. She had the technique, the voice, the swagger. Some called her the “Ivory Queen of Soul.”

But Ray didn’t buy it.

“She’s got the pitch,” he once said, “but not the scars.”

For Ray, soul was not about training or vocal perfection. It was about lived pain, survival, hunger, broken hearts. Teena Marie sang beautifully—but to him, she lacked the invisible bruises that turned music into testimony. She was, in his words, “a clean mirror reflecting everything but retaining no soul.”

George Harrison: The Silent Cut

Ray once covered one of George Harrison’s most famous love songs. Critics hailed it, Frank Sinatra even called it one of the greatest renditions ever recorded.

But when asked, George Harrison gave a cold review: “I like the bridge. The rest didn’t feel right.”

To Ray, those few words cut deeper than any insult. He never performed the song again.

Ray didn’t hate George Harrison. But he hated being treated like a subject for critique rather than a fellow artist who had lived through segregation, blindness, and rejection. “Some people like to keep their love locked up,” Ray said later. “I don’t.”

Justin Timberlake: The Plastic Star

By the early 2000s, Justin Timberlake was being touted as the heir to Michael Jackson. Handsome, choreographed, smooth-voiced—he was a pop industry darling.

Ray listened once to “Cry Me a River.” He turned it off.

“It’s not bad,” he said. “But it’s not alive either.”

Ray wasn’t mocking Timberlake’s skill. He just saw no blood, no smoke, no heartbreak in his voice. To him, Justin represented the ultimate illusion—music engineered by marketing departments rather than forged in pain. “I see a lot of lights,” Ray once said of Timberlake’s generation, “but little illumination.”

The Rest of the List

Other names surfaced in Ray’s final conversations—artists and voices who, in his eyes, symbolized the same betrayal. From white soul imitators to pop stars wrapped in plastic, they all represented what Ray fought against: the hollowing out of music’s truth.

Ray Charles never claimed perfection. He admitted his flaws, his addictions, his failures. But music, to him, was sacred. It wasn’t supposed to be too clean, too polished, too safe. It had to carry scratches, scars, even ugliness—because that’s what it meant to be human.

The Final Roar of an Old Lion

Ray Charles never lived long enough to see today’s debates about cultural appropriation, authenticity, or the commodification of black art. But his words echo louder now than ever.

He wasn’t just pointing fingers at individuals—Elvis, Boone, Bolton, Kenny G, Teena Marie, George Harrison, Justin Timberlake. He was pointing at the system that rewarded imitation over authenticity, polish over pain, whiteness over blackness.

In his last years, when asked about the future of music, Ray gave an answer that summed up his entire philosophy:

“As long as it doesn’t get lulled to sleep.”

Because for Ray Charles, music wasn’t entertainment. It was confession. It was survival. It was life. And for those he couldn’t forgive, the crime wasn’t bad singing. It was making music without a soul.

Full video:

News

“NFL STAR Travis Hunter STUNS Fans, QUITS Football FOREVER After SHOCKING BETRAYAL — Teammate SECRETLY Slept With His Wife and the SCANDAL That No One Saw Coming Has ROCKED the Entire League!”

Travis Hunter’s Shocking Exit: The Jaguars Star, His Wife Lyanna, and the Scandal That Could Shatter a Locker Room When…

“Rapper T.I. BREAKS HIS SILENCE With SHOCKING CONFESSION After His Son King Harris Gets SLAPPED With 5 YEARS Behind Bars — What He Reveals About The Arrest, The TRUTH Behind The Charges, And The DARK FAMILY SECRETS That NO ONE Saw Coming Will Leave You Absolutely Speechless!”

TI’s Worst Nightmare: King Harris Arrested, Facing 5 Years in Prison For years, T.I. warned the world that his son…

At 48, Jaleel White FINALLY Reveals the CHILLING Final Words Malcolm Jamal Warner Whispered to Him Before His Mysterious Death — A Secret He’s Kept Silent For Decades That Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About Their Friendship, Hollywood’s Dark Side, and What Really Happened in Those Final Moments (NEVER Told Until NOW!)

Jaleel White Breaks His Silence: The Untold Story of His Final Goodbye to Malcolm-Jamal Warner The news of Malcolm-Jamal Warner’s…

Christina Ricci Just SHOCKED Hollywood By EXPOSING The DARK Truth About Ashton Kutcher – What She Revealed Has Fans DEMANDING He ROT In Jail… The Secrets, The Lies, And The Scandal That Could Finally END His Career Forever!

Christina Ricci’s Warning and the Dark Shadow Over Ashton Kutcher For years, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis were seen as…

“Ozzy Osbourne’s FINAL Words Before His Death Leave Fans STUNNED – What He Revealed in That Heartbreaking Last Message Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About the Prince of Darkness Forever, and the Truth Behind His Shocking Goodbye Is Sending Shockwaves Across the Music World Right Now!”

Ozzy Osbourne’s Final Act: How the Prince of Darkness Orchestrated His Own Farewell When fans first heard Ozzy Osbourne mutter…

“Kelly Rowland BREAKS Her Silence at 44 – The Stunning CONFIRMATION Fans Have Waited Decades to Hear Is Finally Out, and It’s So Explosive It Could Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé, and the Secret Truth She’s Been Hiding All Along… Until NOW!”

Kelly Rowland’s “Dirty Laundry” of Fame: Secrets, Rumors, and the Shadows of Destiny’s Child For decades, Kelly Rowland has been…

End of content

No more pages to load