James Brown’s Silent Wars: The Six Female Legends He Couldn’t Stand

The Godfather of Soul. The Hardest Working Man in Show Business. The Monarch of Funk. James Brown was remembered by the world as a cultural titan whose roar, sweat, and relentless rhythm redefined American music. But beneath the dazzling footwork, the fiery screams, and the velvet suits was a man perpetually at war—not just with the industry, not just with white America, not even with himself. James Brown fought wars against the very people the public assumed were his allies: his contemporaries in soul, the so-called queens of the same kingdom he helped build.

For Brown, music was not collaboration. It was combat. Every note, every drum kick, every shout had been forged from his survival. He didn’t believe in polish. He didn’t believe in smiles for the camera. And he certainly didn’t believe in voices that floated too gently above the fire of black struggle. His greatest disappointment was not that outsiders misunderstood soul, but that insiders—fellow black icons—diluted it. Six female singers in particular became scars on his legacy. Not enemies in public. Not feuds splashed across tabloids. But quiet wounds he never allowed to heal.

Among them were Tina Turner and Diana Ross, women the world crowned legends. To James, they were distortions—imitations of something primal that he alone embodied. And then there were four others—Janis Joplin, Whitney Houston, and names whispered in rooms but rarely written—who symbolized to Brown the betrayal of soul itself. Their stories with him were not stories of scandal but of silence, of tension so sharp it cut deeper than words.

Diana Ross: Bubblegum Soul

There was no open beef between James Brown and Diana Ross. No heated exchanges, no broken contracts, no lawsuits. Yet his disdain for her was sharper than any headline feud.

New York, 1974. Backstage at the Apollo, a rainy night. His assistant placed Diana’s latest Motown record on a turntable. Brown listened, said nothing for several moments, then sighed and whispered: “Some folks sing soul like it’s bubblegum.”

To most ears, it was critique. To those inside the industry, it was an execution.

For James, Diana Ross embodied everything he loathed about Motown polish. She was flawless, on beat, angelic—but in his eyes, soulless. “She sings like there ain’t a fire outside the window,” he once told a manager. To him, Ross represented black pain packaged for white consumption: velvet-wrapped suffering, aspirations coated in fairy dust, rebellion repackaged as elegance.

Ross wasn’t fake. She had endured her share of hardship. But unlike Brown, who wore scars like a uniform, Diana chose to cover hers in gowns and glamour. For that, he never forgave her.

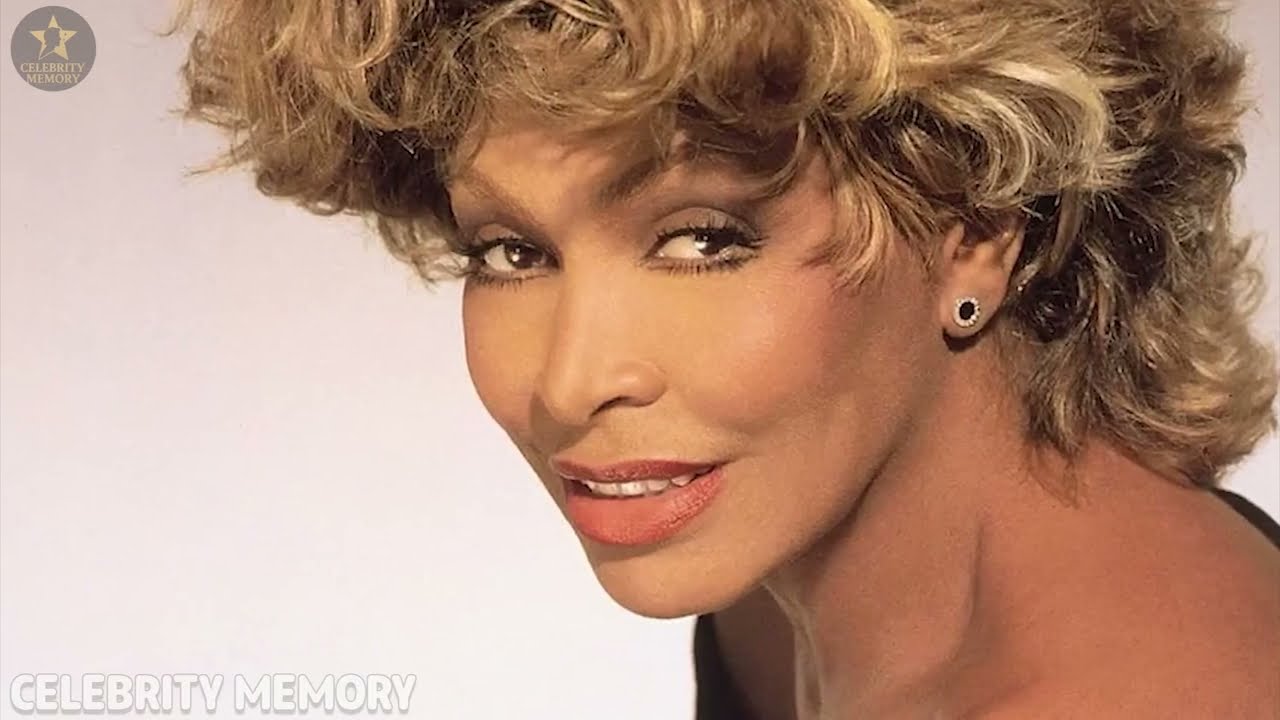

Tina Turner: The Female James Brown?

If Ross represented bubblegum, Tina Turner represented something worse to Brown: imitation.

They never fought publicly, never even exchanged harsh words. Yet Tina haunted James Brown like an echo. She was called the “female James Brown,” a title he never embraced. To him, Tina’s act—hair flying, hips shaking, guttural cries—was his performance softened and repackaged. “They water down the fire and call it sexy,” he once wrote in his memoir.

James roared on stage because no one gave him permission to speak. He danced to shake centuries of chains from his body. When he screamed, he was branded excessive, dangerous, violent. Tina screamed, and she was crowned queen.

The difference wasn’t her gender—it was her acceptance. White audiences adored her fire. Networks broadcast her in prime time. Critics celebrated her as palatable power, a woman fierce but not threatening. Brown resented that deeply. Not because Tina wasn’t good—she was great—but because she could be him without being punished as he was.

Janis Joplin: Pain as Performance

The white world adored Janis Joplin as a raw, authentic voice. They placed her name beside Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin, praising her screams as the gospel of pain. James Brown never accepted that.

“It ain’t just about screaming,” he once muttered. “You got to live it.”

Janis had demons, no doubt—addiction, heartbreak, despair—but to Brown, she was still an outsider. She could choose when to step into darkness. He was born in it. She wailed the blues, but she hadn’t been beaten down by Jim Crow laws, hadn’t carried the burden of black survival with every note.

When she died in 1970, Brown said little. Not grief. Not hatred. Just silence. Because he knew her legend would be cemented more quickly than his, even though she had borrowed from the very well of suffering he considered sacred.

“You can’t wear pain like fashion,” he once said. “It doesn’t fit right unless it scars you.”

Whitney Houston: Too Perfect to Believe

If Ross was bubblegum, Tina imitation, and Joplin appropriation, Whitney Houston was something else: sterilization.

Whitney’s voice was flawless. Her notes soared with divine beauty. Her face glowed like a star designed in a lab. Yet to James Brown, she lacked the essential ingredient: scars.

“She sings from her throat, not from her wounds,” he whispered after one of her triumphant AMA wins.

Brown remembered her as a child, sitting in a studio while her mother Cissy sang backup for him. That girl had eyes full of curiosity. But the superstar Whitney became was molded by record executives, polished into a commercial product. To James, she wasn’t soul—she was pop wearing soul’s clothes.

He didn’t envy her success. He feared what she represented: a future where black music abandoned its roots, where the blood and sweat of survival were replaced by formulas and ballads designed for white acceptance.

When Whitney later struggled with addiction, the same press that adored her turned cruel. Brown saw it and said nothing, but deep inside, he felt confirmation: the world had loved her when she was perfect, and abandoned her the moment she bore scars.

The Silent Wars

James Brown never launched public crusades against these women. He didn’t record diss tracks. He didn’t seek headlines. His war was silent, his verdicts delivered in cold stares, faint mutters, and absences. He didn’t hate women—he revered Aretha Franklin, Patti LaBelle, and Lyn Collins, women whose voices carried the rawness he respected. What he couldn’t stand were singers who, in his eyes, transformed survival into performance, who polished pain until it shined too brightly for him to trust.

Behind the glitz of the 1960s and 70s soul explosion, there was a deeper conflict: what did it mean for music to be authentic? To Brown, authenticity wasn’t about talent. It was about scars. You couldn’t sing of freedom if you’d never felt chains. You couldn’t sing of heartbreak if your heart hadn’t been shattered. You couldn’t sing of struggle if you’d never clawed your way out of it.

Tina, Diana, Janis, Whitney—each in their own way—represented to him a betrayal of that authenticity. Not because they lacked talent, but because their talent had been shaped into something the world could consume without discomfort.

Legacy of a Relentless Judge

James Brown died in 2006, still the Godfather, still the monarch. But his silent wars never ended. Even in his later years, when asked about the new generation of singers, he muttered only: “I regret that the next generation no longer knows how to hurt.”

It wasn’t bitterness. It wasn’t envy. It was grief—the grief of a man who believed he had bled so future artists wouldn’t have to, but who then felt betrayed when they sang as if the bleeding had never happened.

He never forgave Diana Ross’s perfection. He never forgave Tina Turner’s softened imitation. He never forgave Janis Joplin’s borrowed pain. He never forgave Whitney Houston’s polish. And maybe, in truth, he never forgave a world that allowed them to be adored for what he was condemned for.

James Brown didn’t hate women. He didn’t hate success. He hated a world where soul—the sound of survival—was turned into spectacle. He fought his battles not with press releases but with silence, leaving behind stories only whispered in dressing rooms, in rehearsal halls, in tapes marked raw that never aired.

In the end, his verdict was simple: Soul was not a genre. Soul was a wound. And unless you carried that wound every day of your life, James Brown would never truly believe you.

Full video:

News

“NFL STAR Travis Hunter STUNS Fans, QUITS Football FOREVER After SHOCKING BETRAYAL — Teammate SECRETLY Slept With His Wife and the SCANDAL That No One Saw Coming Has ROCKED the Entire League!”

Travis Hunter’s Shocking Exit: The Jaguars Star, His Wife Lyanna, and the Scandal That Could Shatter a Locker Room When…

“Rapper T.I. BREAKS HIS SILENCE With SHOCKING CONFESSION After His Son King Harris Gets SLAPPED With 5 YEARS Behind Bars — What He Reveals About The Arrest, The TRUTH Behind The Charges, And The DARK FAMILY SECRETS That NO ONE Saw Coming Will Leave You Absolutely Speechless!”

TI’s Worst Nightmare: King Harris Arrested, Facing 5 Years in Prison For years, T.I. warned the world that his son…

At 48, Jaleel White FINALLY Reveals the CHILLING Final Words Malcolm Jamal Warner Whispered to Him Before His Mysterious Death — A Secret He’s Kept Silent For Decades That Could Change Everything We Thought We Knew About Their Friendship, Hollywood’s Dark Side, and What Really Happened in Those Final Moments (NEVER Told Until NOW!)

Jaleel White Breaks His Silence: The Untold Story of His Final Goodbye to Malcolm-Jamal Warner The news of Malcolm-Jamal Warner’s…

Christina Ricci Just SHOCKED Hollywood By EXPOSING The DARK Truth About Ashton Kutcher – What She Revealed Has Fans DEMANDING He ROT In Jail… The Secrets, The Lies, And The Scandal That Could Finally END His Career Forever!

Christina Ricci’s Warning and the Dark Shadow Over Ashton Kutcher For years, Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis were seen as…

“Ozzy Osbourne’s FINAL Words Before His Death Leave Fans STUNNED – What He Revealed in That Heartbreaking Last Message Will Change Everything You Thought You Knew About the Prince of Darkness Forever, and the Truth Behind His Shocking Goodbye Is Sending Shockwaves Across the Music World Right Now!”

Ozzy Osbourne’s Final Act: How the Prince of Darkness Orchestrated His Own Farewell When fans first heard Ozzy Osbourne mutter…

“Kelly Rowland BREAKS Her Silence at 44 – The Stunning CONFIRMATION Fans Have Waited Decades to Hear Is Finally Out, and It’s So Explosive It Could Change Everything You Thought You Knew About Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé, and the Secret Truth She’s Been Hiding All Along… Until NOW!”

Kelly Rowland’s “Dirty Laundry” of Fame: Secrets, Rumors, and the Shadows of Destiny’s Child For decades, Kelly Rowland has been…

End of content

No more pages to load