The $400 Million Hypocrisy: How Jim Kelly, Hollywood’s First Black Action Icon, Died Fighting His Own Bills

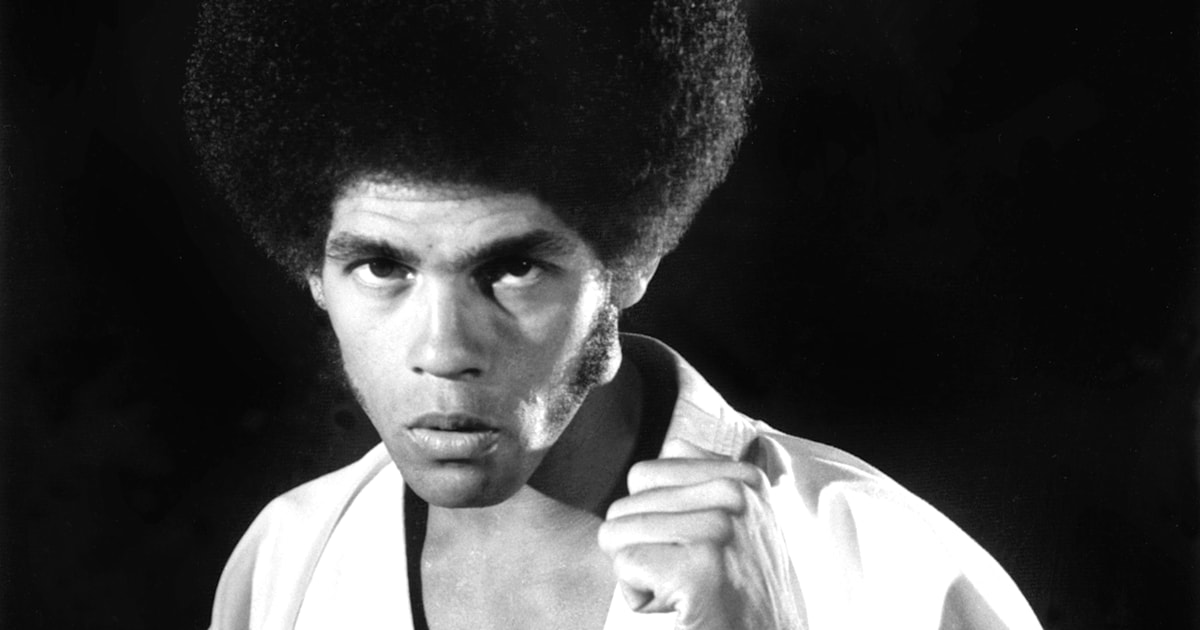

On June 29th, 2013, the world lost a legend whose swagger, skill, and sheer defiance helped reshape the global image of the black man on the silver screen. Jim Kelly, America’s first black martial arts icon, passed away in San Diego at the age of 67. The news, while sad, felt like the quiet closing of a monumental chapter. An era defined by the explosive, groundbreaking energy of 1970s cinema had ended.

But beneath the respectful tributes and nostalgic memorial posts lay one of Hollywood’s cruelest, most enduring ironies. The man who had paved the way for an entire generation of black actors, whose films had once earned Warner Brothers hundreds of millions of dollars, died with a modest fortune—one so disproportionately small that his family reportedly faced difficulty covering the final hospital bills and legal paperwork.

Jim Kelly, the celebrated “Black Samurai,” left the world a sprawling, priceless cultural legacy, but he left his family a financial tragedy soaked in tears. His life was a testament to uncompromising pride, but his death became a stark, devastating lesson in the systemic economic betrayal faced by black pioneers in the ruthless machinery of the entertainment industry.

The Boy Who Refused to Kneel

To understand the pride Kelly protected so fiercely, one must return to his origins. Born James Milton Kelly on May 5th, 1946, in Paris, Kentucky, he grew up in a segregated era where equality was a distant promise. His early life was defined by the pervasive prejudice that marked the American South in the 1950s.

Young Jim was fast, strong, and smart, choosing to fight the suffocating world of segregation through sports. At Bourbon County High School, he was a star in basketball, track, and football. His talent was so undeniable that it earned him a full football scholarship to the University of Louisville—an extraordinary achievement for a young black man at the time.

Yet, Kelly’s pride was non-negotiable, even at the cost of his future. In 1965, during a practice, the head coach hurled a racist insult at another black player. Kelly’s reaction was immediate and definitive: he threw his helmet to the ground, confronted the coach, and walked out. “If that’s how you lead, then I don’t need to play for you,” he declared, never looking back, never apologizing.

That single decision cost him everything: his scholarship, his path out of poverty, and his easiest route to success. But Jim Kelly chose to lose it all just to keep his dignity intact.

The Black Dragon Rises in Crenshaw

After leaving college, Kelly drifted, eventually landing in Los Angeles. It was there, in a small dojo, that he found his true calling. Martial arts offered him a sanctuary where “everyone was equal before the punch,” regardless of color or origin. He trained relentlessly under masters like Sin Kuang The and Parker Shelton, embracing an intensity that shocked even seasoned fighters. He practiced eight hours a day, famously saying, “Pain heals. But if you quit, that wound stays with you forever.”

Within five years, the former football player was a world-class champion. In 1971, at the Long Beach International Karate Championships, Kelly defeated multiple opponents to win the World Middleweight Championship. The sight of a black martial artist beating Asian fighters on an international stage was unprecedented, opening doors that segregation had once bolted shut.

He moved to Los Angeles and opened his own dojo on Crenshaw Boulevard, turning it into a sanctuary for young black men and women, teaching discipline and self-respect. In Crenshaw, he was Sensei Jim, a living example of a dream redeemed through sheer will. This dojo became the stage for his next, world-changing act.

The Kick That Shook Hollywood

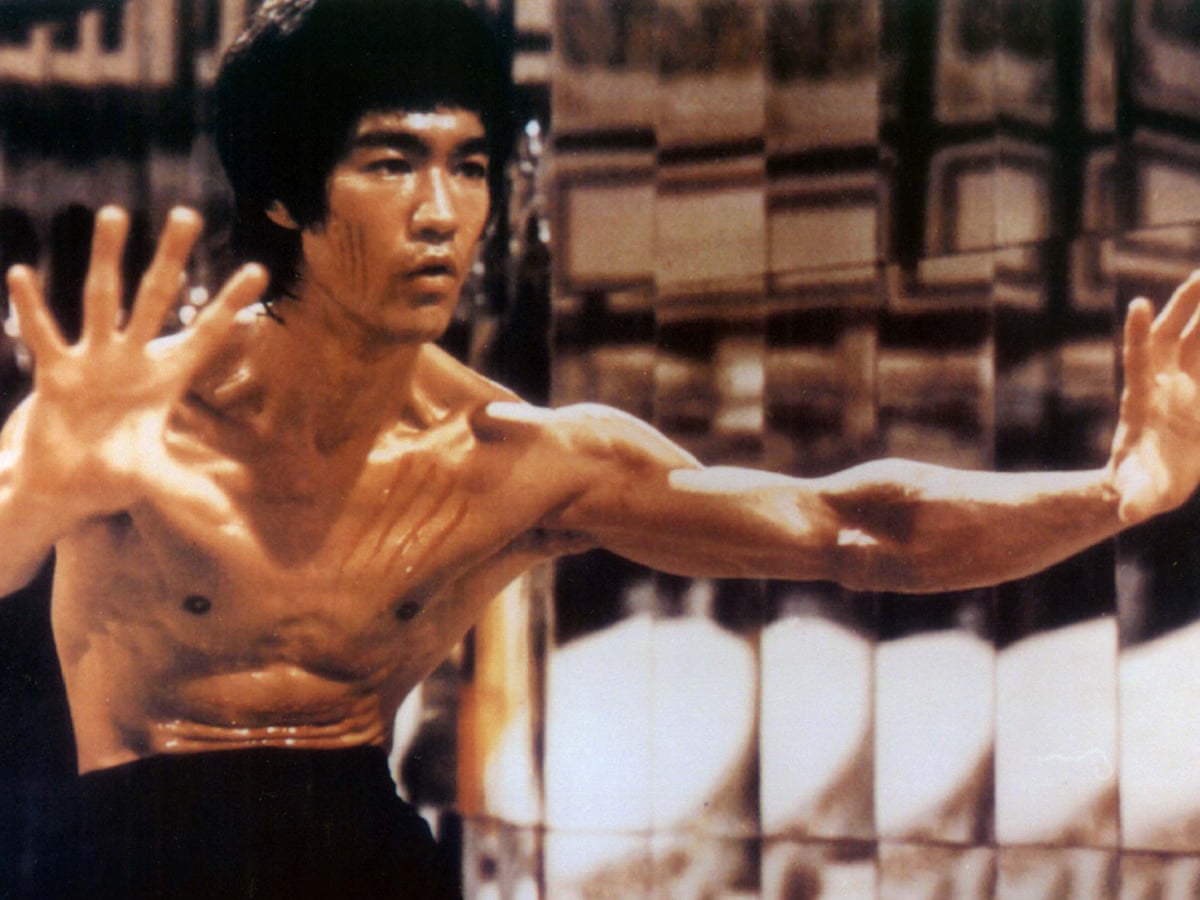

In early 1972, a Warner Brothers producer named Fred Weintraub, fresh off the success of the Kung Fu TV series, heard whispers of a black martial artist who moved like lightning. He sought Kelly out. When Kelly spun and unleashed a kick, Weintraub was instantly stunned: “My God, he looks like he just stepped out of a comic book.”

A week later, Jim Kelly was on a plane to Hong Kong, signed to co-star in Enter the Dragon. On set, despite being the only black man in the main cast, he found an ally and a peer in Bruce Lee, who called him “Brother Jim.” Kelly’s role as Williams, an American martial artist, was initially minor, but his magnetic energy and cool defiance quickly led director Robert Clouse to expand it.

When Enter the Dragon premiered in August 1973, it became a global sensation, grossing over $90 million worldwide—the equivalent of more than $400 million today. To black audiences, Kelly was an instant hero: the first man in cinema history to punch back at the system, radiating an attitude of black power and cool defiance. Theaters in Harlem and Detroit erupted every time he appeared. The media crowned him the “Black Samurai,” and Jet magazine put him on the cover with the headline, “The new face of black power on screen.”

Kelly’s presence was a profound political statement without uttering a single word about race. His kicks spoke for millions, proving that black men could be symbols of power and dignity, not just victims.

The Cruel Fine Print: An Empire Built on Sand

The glory was immense, but the financial reward was negligible. While Warner Brothers counted profits in the hundreds of millions, Jim Kelly was counting bills.

According to those close to him, Kelly’s share from the global blockbuster, Enter the Dragon, was “barely enough to buy a small house in Sherman Oaks and a used sports car.” His contract was a standard “scale contract,” the pay rate for B-list actors: between $1,000 and $2,500 a week. Crucially, it contained no box office percentage, no residual rights, and no international royalties.

Kelly knew the score. When reporters asked about the money, he stated bluntly in a 1974 interview, “They got rich off that movie. All I got were bigger tax bills.” A simple sentence that exposed the systemic fraud: a black man helped a studio make a fortune and still couldn’t afford a decent home in Beverly Hills.

Despite the injustice, Warner Brothers capitalized on his fame, signing him for a three-picture deal: Black Belt Jones (1974), Three the Hard Way (1974), and Hot Potato (1976). He was the perfect blend of Shaft‘s cool and Bruce Lee’s fighting spirit.

But the Jim Kelly empire was built on sand. The studio kept sending him nearly identical scripts, featuring silent black characters who fought well but lacked substance. When Kelly, driven by his lifelong pride, asked to rewrite the dialogue to give his characters more soul and voice, the producer’s response was chillingly dismissive: “Audiences don’t want to hear you talk. They just want to see you fight.”

Kelly refused the muzzle. “I don’t act to be a statue,” he replied, “I act to tell our story.” From that moment, the death sentence of the industry was applied: he was labeled “difficult to work with.” In an industry where the power was exclusively held by white men, this label was career suicide. By 1975, the Blaxploitation wave had collapsed, and Hollywood turned its attention to a new wave of heroes—Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van Damme—heroes that fit white America’s taste.

Kelly stopped receiving calls. The projects he wrote were rejected. When asked why he left Hollywood in 1978, he smiled with both fatigue and pride: “I didn’t leave Hollywood. Hollywood left me.” He was dropped, not due to lack of talent, but because the game was never built for him to win.

Sanctuary on the Tennis Court

In March 1977, Jim Kelly quietly withdrew. He drove his faded sports car south to San Diego, leaving behind the torn contracts, the movie posters, and the city that had worshiped and then strangled him. He found his freedom not in a dojo, but on a tennis court.

Kelly disappeared from the headlines and immersed himself in the sport, joining the USA Senior Men’s Circuit. He turned his discipline and agility into a new pursuit, quickly ranking among the top singles and doubles players in California. More importantly, he turned his passion into a sustainable business, founding and later owning the Coronado Bay Tennis Club.

This club became his sanctuary—a place of wind, sun, and peace that Hollywood had never allowed. It provided a steady, honest income, estimated between $60,000 and $100,000 per year, enough to support a comfortable, quiet life with his wife, Marilyn Dishman, whom he married after reconnecting with the old friend from his Kentucky high school days.

The internet, however, painted a mythical picture, claiming his net worth was $20 to $25 million USD. The truth, compiled from property and pension records, was far more modest: Jim Kelly’s total net worth was estimated between $1.5 million and $2.5 million. It was enough for a comfortable retirement, but nowhere near the myth, and certainly nowhere near the $400 million he helped generate.

A man who helped a studio earn a fortune ended up with less than three percent of the value he created.

The Final, Silent Battle

As his hair turned gray, his expenses climbed relentlessly: property taxes, court maintenance, and steadily rising health insurance costs. He never complained, but a friend once recalled, “I knew there were times he had to dip into his savings just to pay the land lease.” The former million-dollar star was quietly counting bills to keep the small court where he taught children to play tennis.

In 2011, the final battle began. Kelly was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He chose to face the disease in silence, refusing to become the frail celebrity Hollywood might pity. He continued driving to the tennis club every morning, his iconic afro hair falling away from the chemotherapy.

The battle was not just physical; it was financial. His insurance, based on a short, decades-old film career, only covered a fraction of the costs, which totaled hundreds of thousands of dollars each year. He sold parts of his club lease, borrowed against his life insurance, and depleted his savings. Friends offered to start a fundraiser, but Kelly flatly refused. “I don’t want anyone’s pity,” he said. “I made my living with my kicks, and I’ll pay my way with them too.”

He was poor, a close friend said tearfully, but he never let anyone know. Even at the end, he fought to stay strong in the eyes of the world.

When Jim Kelly passed away peacefully at his home on June 29th, 2013, he had won the fight for his soul, but he had lost the fight against the financial weight of his bills. His funeral was small, private, without media. But his legacy exploded one last time. Hundreds of fans at Comic-Con International 2013 raised their old Enter the Dragon posters, his proud afro and cold, fearless eyes staring back through time.

He never won an Oscar or got a star on the Walk of Fame, but Jim Kelly had something every award longs to represent: integrity. He didn’t just break the color barrier; he broke the line between celebrity and human being. He chose to step out of the spotlight to keep his soul, and in a world where fame shifts every hour, that choice made him immortal. His name outlived his fame because he left behind the rarest thing in Hollywood: the truth.

News

The Perfect Image Cracks: Blake Lively’s Secret History of Feuds and the Hypocrisy Dividing Hollywood

The collision between a carefully constructed celebrity image and a tumultuous history of behind-the-scenes conflict is currently threatening to…

EBT Card to $100 Million Tour: The Tragic Fall of Kevin McCall and Chris Brown’s Icy Feud, Exposed by a Viral Breakdown

The world of R&B and hip-hop was recently forced to confront a brutal truth about the volatility of fame,…

From ‘Cap’ to Courtroom: Lil Meech’s Reputation Shattered as Legal War Erupts Over Explosive Relationship Claims

The collision between celebrity status and the harsh reality of social media scrutiny has claimed another high-profile victim, and…

The Gilded Cage: Dame Dash Exposes Beyoncé’s Secret Affair with Bodyguard Julius, Claiming the Carter Marriage Was Pure Business

For nearly two decades, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter and Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter have reigned as the most powerful and, ostensibly, the…

The $20 Million Betrayal: Yung Miami Sues Tyla Over ‘Stolen’ Hit, Exposing the Dangerous Cost of Sharing Unreleased Music

In an industry where collaboration often walks a precarious line with exploitation, the latest legal earthquake has sent shockwaves across…

The Curse of Cash Money: Toni Braxton Exposes Birdman’s Dark Secrets, Alleged Rituals, and the Empire That Eats Its Own

The relationship between R&B royalty Toni Braxton and hip-hop mogul Bryan ‘Birdman’ Williams was always a paradox. It was an…

End of content

No more pages to load